Who owns the Coal?

Last time, we talked about what's happening to coal generators in the U.S, and we quickly found that they were getting old, and nobody was building any new ones because they are too expensive. That naturally leads to the question: Who still owns coal, and what are they doing with it? Once again, let's pop up Hyaline and get cracking.

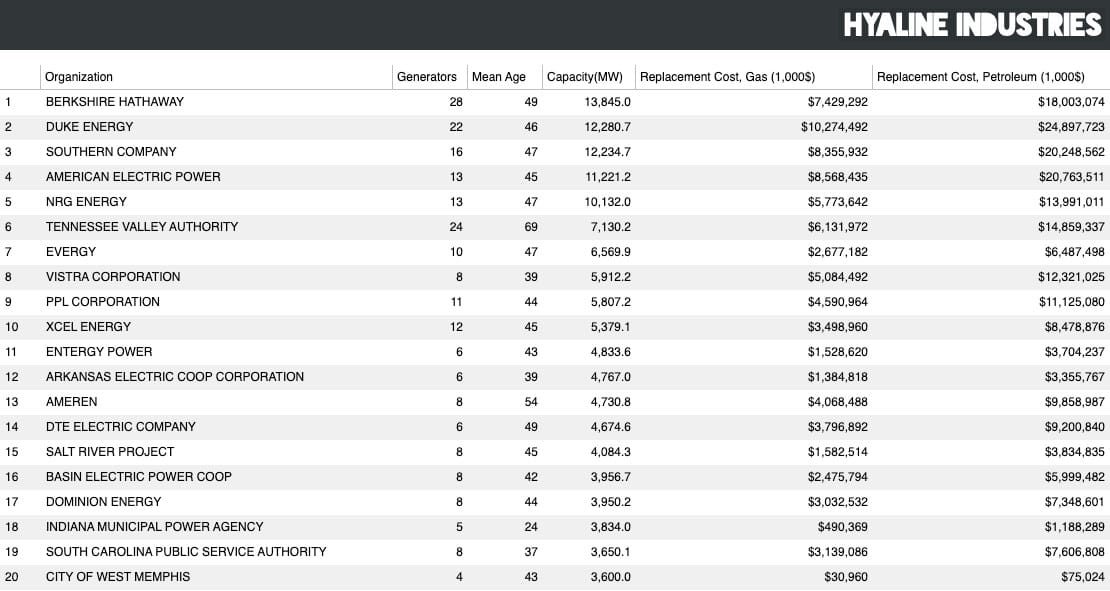

First, we quickly get ourselves a list of companies which still have at least some kind of ownership over a coal generator in 2023:

These are the 20 organizations with the largest amount of coal still running, sorted by capacity. Notice that this list has a lot of holding companies--that's because we roll up all the little subsidiaries we track into the single controlling entity.

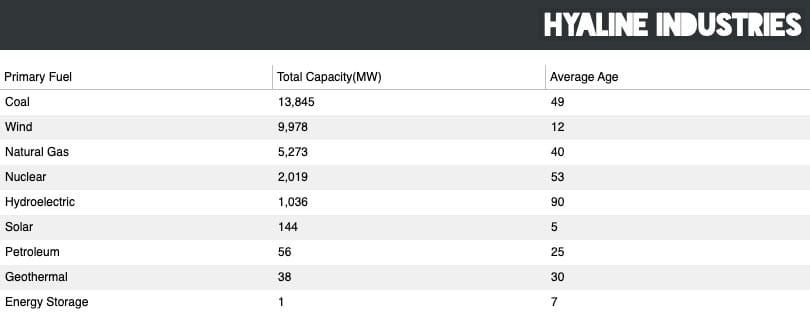

At the top we have Berkshire Hathaway. In 1999, BH acquired MidAmerican Energy, and in 2005 it acquired Pacificorp, both of whom held a lot of power assets:

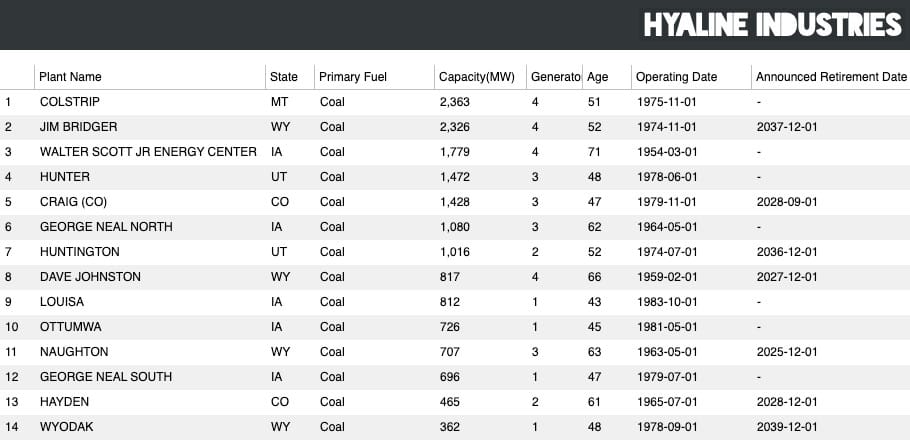

Coal is a big part of their portfolio, but with a high average age that makes it worth exploring a bit. Here are the actual plants that BH currently operates:

Almost instantly we see that a lot of it is scheduled for retirement: 3.4 GW before 2030, and another 3.7 GW before 2040. By then basically everything they own except the Walter Scott Jr Energy Center will be at its end-of-life(except the Walter Scott Jr Energy Center, which added a generator in 2007), and will probably also be retired or slated for retirement. And just like every other company in the U.S., Berkshire Hathaway isn't building more.

That's kinda boring, honestly. Berkshire Hathaway has some old coal assets, and they are slowly retiring them. Yawn. Let's try for a comparison with the #2 company on our list: I wonder what Duke Energy is doing.

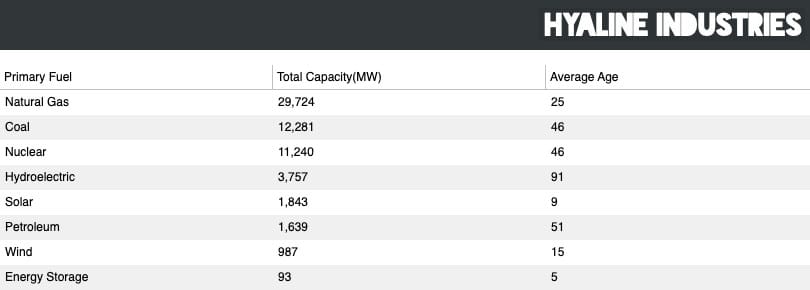

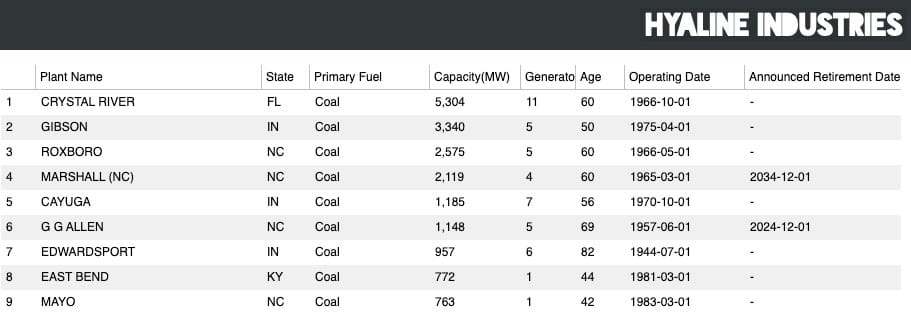

Once again, let's just look at their current portfolio:

Looks like their coal assets are roughly the same age as Berkshire Hathaways, and they have slightly less, but a comparable amount of capacity. Duke's coal capacity is concentrated in just 10 plants across the south and southern midwest, and all of those plants are over 40 years old, but only two are scheduled for retirement--one did in fact retire at the end of 2024. But overall, there aren't very many differences between Duke and Berkshire Hathaway.

So what gives? Berkshire Hathaway is explicitly exiting the coal business, while Duke is hanging on, even while they both have comparably aged and sized fleets.

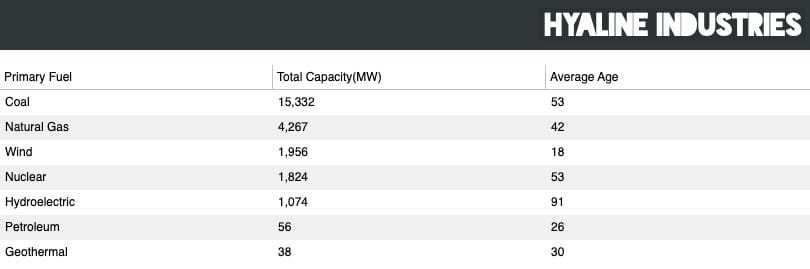

Things are made slightly clearer if we look back in time. In 2008, This was Berkshire Hathaway's energy portfolio:

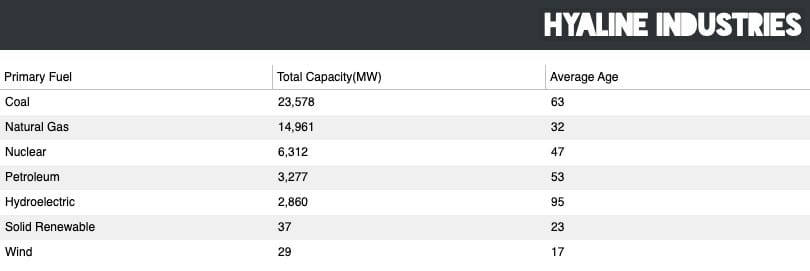

and here is Duke's:

Some of the difference is just timing– Berkshire Hathaway's coal fleet in 2008 was slightly younger than Duke's, and Duke did shed close to 13GW of capacity, while Berkshire Hathaway only shed about 2 GW. So Duke did shrink their coal portfolio already, by a lot. Arguably, Duke is ahead of Berkshire Hathaway on this.

But that's not much of an explanation for why Duke is keeping the rest of their fleet running. The question remains: Why are these two companies making such wildly different choices with their coal fleet?

There are two theories that come to mind:

- Berkshire Hathaway is a participant in ISO markets--MISO especially, while Duke is a vertically integrated utility(although it participates in SEEM). Perhaps a market encourages a company to retire their coal?

- Duke's plants are in the south and southeastern midwest, while Berkshire Hathaway's are all in the upper midwest and great plains. Perhaps there is something about the south that encourages coal, or something about the Midwest that makes coal less profitable.

In another article, we'll have a look at power by location, and see if we can figure out which of these answers explains it, or even if there is a third possibility.